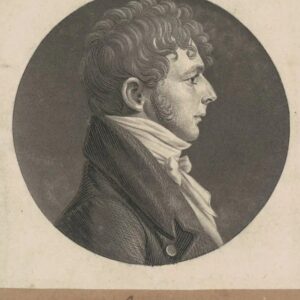

Our Namesake

Andrew Sterett (January 27, 1778 – January 9, 1807) was an officer in the United States Navy during the nation’s early days. He saw combat during the Quasi-War with France and in the Barbary Wars, commanding the schooner USS ENTERPRISE in both conflicts.

EARLY LIFE

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Andrew Sterett was the son of John Sterett, a former Revolutionary War captain and a successful shipping merchant. The fourth of ten children, he nevertheless inherited a sizable amount of money. Despite this, he resolved to join the Navy, and was commissioned as a lieutenant on 25 March 1798.

THE QUASI-WAR

Sterett’s first assignment was as Third Lieutenant of the USS CONSTELLATION, under Captain Thomas Truxtun, which was sent to do battle with French vessels during the Quasi-War. He was commanding a gun battery when USS CONSTELLATION defeated and captured the French frigate Insurgente on 9 February 1799. Insurgente lost 29 dead and 41 wounded; the only American loss was a seaman run through by Sterett’s saber in a summary execution, the seaman, Neal Harvey, having abandoned his post in a panic. Upon USS CONSTALLATION’s arrival back in Baltimore, the anti-federalist press, who opposed the military in general and the Quasi-War in particular, seized upon this incident as an example of the Navy’s “arrogance and cold-bloodedness.” The objections intensified when Sterett was heard to say, “We put men to death for even looking pale on this ship.” The Navy saw things quite differently, and soon promoted Sterett to the rank of First Lieutenant. A year later, Sterett was involved in a battle to a draw with the 54-gun French frigate Vengeance.

In May 1800, Sterett reports onboard the newly launched USS PRESIDENT as first lieutenant. USS PRESIDENT was a three-masted 44-gun heavy frigate and the last of the U.S. Navy’s first six heavy frigates to be built.

On 27 October 1800, he took command of the schooner USS ENTERPRISE where he remained through the end of the Quasi-War, capturing the privateer Amour de la Patrie on 24 December 1800 (read the history of the schooner ENTERPRISE on Wikipedia here).

THE BARBARY WARS

After resupplying in Baltimore, Sterett sailed USS ENTERPRISE to the Barbary Coast in June 1801, as part of a force under Commodore Richard Dale, in the first stages of the Barbary Wars.

On 1 August 1801, USS ENTERPRISE under Sterett’s command handily defeated the 14-gun Tripoli, a Tripolitan corsair. After twice faking surrender, Tripoli suffered 30 dead and 30 wounded, including the Captain, Rais Mahomet Rous, and the first officer. USS ENTERPRISE suffered no casualties. Since there was no formal declaration of war, USS ENTERPRISE was under orders not to take prizes. After her crew was ordered to dump its guns overboard, Tripoli was allowed to sail home, where her captain was humiliated and punished (read the history of the Barbary Wars here).

USS ENTERPRISE was sent back to Baltimore with dispatches after this engagement. While there, on the recommendation of Congress, Sterett was presented by President Thomas Jefferson with a sword in gratitude of the victory over the Tripoli. (read the congratulatory letter sent from President Thomas Jefferson to Andrew Sterett on 1 December 1801 available at the National Archives here). USS ENTERPRISE’s crew was also rewarded with an extra month’s pay. The ship returned to the Mediterranean in November 1802. (read poem written Andrew Sterett called Sterret’s Sea Fight here).

Ship movements of the Enterprise during the Barbary Wars here.

Following several more dispatches to the coast of Tripoli, Sterett and the USS ENTERPRISE witnessed the return of freedom of the seas in the Mediterranean for American ships. Sterett relinquishes command of the USS ENTERPRISE to Lt. Isaac Hull March 1, 1803, and is promoted to master commandant May 20, 1804, a rank authorized between lieutenant and captain in 1799.

RESIGNATION

In June 1805, Master Commandant Andrew Sterett is offered the command of a brig USS HORNET, a single-masted, wooden-hulled sailing sloop-of-war of the United States Navy which was under construction. Sterett had been senior in rank to Lt. Stephen Decatur, Jr., but due to their comparative length of service, Decatur was selected to be promoted to Captain above Sterett. Sterett therefore submitted his resignation from the Navy June 29, 1805, and was accepted “with regret” by the Navy Department on July 5, 1805.

FINAL VOYAGE

In August 1806, Sterett was hired by Baltimore ship owner Lemuel Taylor to captain Taylor’s sloop Warren on a trading voyage to the Northwest coast of America and China (though there were rumors that the ship was actually headed to the West Indies or South America with a cargo of contraband). Taylor selected Procopio Pollock, son of Revolutionary War financier Oliver Pollock, as the Warren’s supercargo (cargo master). Both men were given sealed orders that were not to be opened until a certain point in the voyage.

On 12 September the Warren sailed out of Baltimore with a complement of about 112 men, including four officers (all previously known to Sterett. In early December, off the coast of Brazil, Sterett and Pollock opened their instructions. To his horror Sterett discovered that Taylor’s orders to Pollock gave Pollock control over not only the cargo but operational control of the vessel as well; they stated that the ship was to proceed to the west coast of South America, where Pollock was to engage in trade as he saw fit. These orders, different from those given to Sterett and in violation of the articles of employment signed by the crew, caused a violent argument between Sterett and Pollock. Sterett seems to have been driven into a frenzy bordering on madness; he was heard by members of the crew to say that before he would follow such orders, he would kill either Pollock or himself. About a week later, after apparently trying unsuccessfully to shoot Pollock, Captain Sterett retired to his cabin alone and shot himself in the head. He lingered in agonizing pain for two weeks before dying on 9 January 1807, a few weeks shy of his 29th birthday and shortly before the ship rounded Cape Horn. Neither the records of the Warren or a lawsuit later filed against Taylor by the crew make any mention of Sterett’s body, so it is presumed that he was buried at sea. Thus ended the short life of an officer of great principle and promise.

Further reading:

Our First Real War by Montgomery N. Kosma